The COC Protocol is an individualized therapeutic approach which seeks to simultaneously target multiple cancer pathways. The COC Protocol may be considered in patients with blood cancers, adjunctive to conventional cancer treatments.

Care Oncology has been treating patients since 2013. Our oncology clinician are experienced in working with many patients with different types of cancer, and alongside many standard-of-care regimens. We understand that cancer is a very personal condition, and every patient has a unique set of challenges. Please get in touch with us to discuss your individual situation further.

Metabolism is the conversion of food to energy to run cellular processes and construct cellular building blocks. It is widely accepted that the metabolism of cancer cells is usually fundamentally different to that of healthy non-cancerous cells. Altered metabolism is now considered a hallmark of cancer and a new discipline of “metabolic oncology” has emerged (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000; Hanahan and Weinberg 2011; Bergers and Fendt, 2021).

Cancer cells need large amounts of energy to survive and grow. They commonly use an adaptive process called aerobic glycolysis (the ‘Warburg effect’) to generate the excessive energy they need (Kroemer and Pouyssegur, 2008; Liberti and Locasale, 2016). The COC Protocol aims to target various molecular processes involved in and surrounding aerobic glycolysis and cancer metabolism. It aims to restrict cancer cell energy supply and use, while simultaneously preventing the cells from adapting and using other pathways to take up energy.

As a result of ongoing metabolic stress, the overall metabolic rate of the cancer cell could be lowered (Jang et al., 2013), and cancer cells may become weaker and less able to take in and use nutrients they need from their surroundings (e.g., glucose, lipids, and essential amino acids such as glutamine and arginine). This may potentially make it more difficult overall for cancer cells to survive, grow, spread, and adapt to changing conditions in the body (Martinez-Outschoorn et al., 2017, Jagust et al, 2019, Guerra et al., 2021).

Gradually, metabolically-weakened cancer cells (including more resilient and previously treatment-resistant cells) can potentially become more vulnerable to attack from other cell-killing cancer therapies such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and other therapies (Luo and Wicha, 2019, Zhao et al, 2013, Butler et al, 2013).

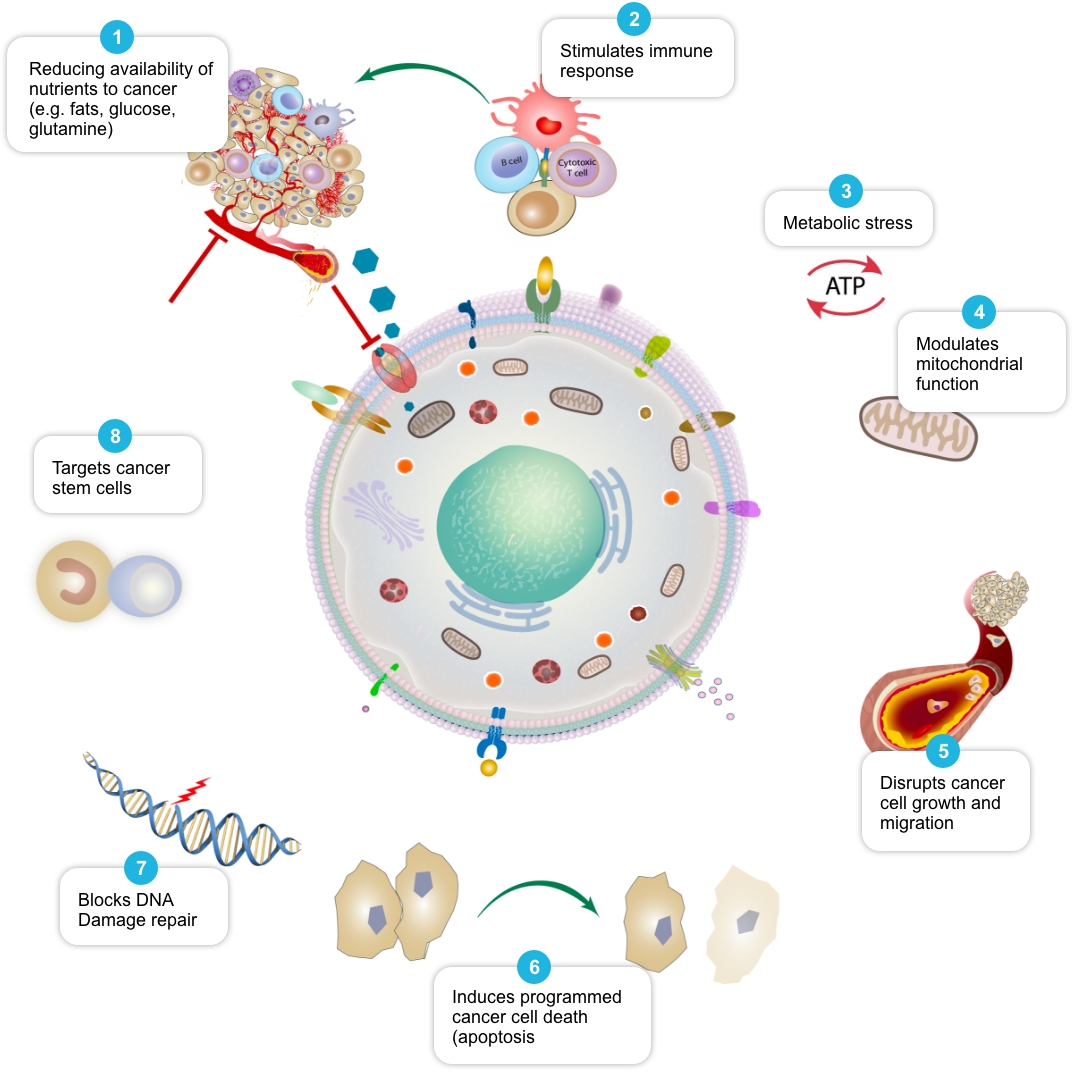

Review of peer-reviewed literature suggests that each individual element of the COC Protocol may target cancer cell metabolism in a distinct and potentially complementary way, and we have termed this action ‘mechanistic coherence’. Put simply, mechanistic coherence describes the possibility of attacking a cancer cell from different angles in what may be a synergistic or additive fashion. This type of combination approach in cancer is discussed by Mokhtari et al, 2017, and others.

| Mechanism1 | Selection of Published Papers |

| Reduce availability of nutrients to cancer cell | Rosilio C. et al. 2014 PMID: 24462823, Babcook M.A. et al. 2016. PMID: 27441003 |

| Stimulate and facilitate immune response to cancer cell | Al Dujaily E. et al. 2020. PMID: 32190817, Yongjun Y. et al. 2013. PMID: 23707077, Blom K. et al. 2017 PMID: 28472897, Bahrambeigi S. et al. 2019 PMID: 31884044, Eikawa S. et al. 2015. PMID: 25624476, Kurelac I. et al. 2019 PMID: 31091466, Lucero-Diaz P.A. et al. 2016 (Abstract), Tang H. et al. 2013 PMID: 23282955 |

| Place cancer cells under ‘metabolic stress’ | Pernicova I. et al. 2014. PMID: 24393785, Clendening J.W. et al. 2012. PMID: 22310279, Guerra B. et al. 2021 PMID: 33718197, Huang B. et al. 2020. PMID: 32694690, McGregor G.H. et al. 2020 PMID: 31562248, Petővári G. et al. 2018 PMID: 30574020 |

| Modulate mitochondrial function in cancer cells | Ozsvari B. et al. 2017 PMID: 29080556, Cazzaniga M. et al. 2015 PMID: 26605341, Missiroli S. et al. 2020 PMID: 32818805, Dijk S.N. et al. 2020 PMID: 32152409 |

| Disrupt cancer cell growth and migration | Kamarudin M.N.A. 2019. PMID: 31831021, Jiang W. et al. 2021. PMID: 34303383, Mukhopadhyay T. 2002 PMID: 12231542, Pinto L.C. et al. 2015 PMID: 26315676, Yang B. et al. 2015 PMID: 26111245 |

| Induce programmed cancer cell death (apoptosis) | Song H. et al. 2014 PMID: 25502932, Doudican N. et al. 2008 PMID: 18667591, Sasaki J. et al. 2002 PMID: 12479701, Bayat N. et al. 2016 PMID: 27836464, Cafforio P. et al. 2005 PMID: 15705602, Fromigué O. et al. 2006 PMID: 16470222, Kalinsky K. et al. 2017 PMID: 27305912, Jiang W. et al. 2021. PMID: 34303383 |

| Block cancer cell DNA damage repair | Efimova E.V. et al. 2018 PMID: 29030460, Lamb R. et al. 2015 PMID: 26087309, Peiris-Pagès M. et al. 2015 PMID: 26425660 |

| Slow growth of tumor-feeding blood vessels (anti-angiogenic activity) | Bai R.-Y. et al. 2015 PMID: 25253417, Orecchioni S. et al. 2015 PMID: 25196138, Qian W. et al. 2018 PMID: 30053447 |

| Target cancer stem cells and may help make them more vulnerable to standard cancer treatments | Saini et al. 2018. PMID: 29342230, Brown et al. 2020 PMID: 32369446, Hirsch H.A. et al. 2009. PMID: 19752085, Scatena C. et al. 2018 PMID: 30364293, Yang B. et al. 2015 PMID: 26111245, Bayat N. et al. 2016 PMID: 27836464, Kato S. et al. 2018 PMID: 29848667, Kodach L.L. et al. 2011 PMID: 21551187, Jiang W. et al. 2021. PMID: 34303383, vMarkowska A. et al. 2019 PMID: 31054863, |

| 1 This table is a summary of some of the potential mechanisms of action reported for agents used in the COC Protocol as reported in the scientific literature. This is an evolving field of research, and this list is not exhaustive. | |

Care Oncology

3705 Saunders Avenue

Richmond, VA 23227

info@careoncology.com

Care Oncology Clinic

76 Harley Street

London

W1G 7HH

+44 (20) 4519 0630

info@careoncology.eu

© 2023 Care Oncology – A StageZero Company. All rights reserved.

Leave North American website?

Yes, I would like to continue to the new site: https://careoncologyclinic.com/

Leave North American website?

Yes, I would like to continue to the new site: https://careoncologyclinic.com/

Leave North American website?

Yes, I would like to continue to the new site: https://careoncologyclinic.com/

Leave North American website?

Yes, I would like to continue to the new site: https://careoncologyclinic.com/